Have you ever wondered about the most common terms in financial trading? Let’s check it out.

Arbitrage

Bear Market

Bull Market

Candlestick

Day Trading

FOMO

HODL

Liquidity

Market Order

Resistance

Support

Volatility

Arbitrage

Arbitrage is a trading strategy that aims to profit from price discrepancies of the same asset on different exchanges or markets. It involves the following key principles:

Price Differences: Arbitrage opportunities arise when the same asset (e.g., a cryptocurrency like Bitcoin) is trading at different prices on different exchanges or in different markets. These price differences can occur due to various factors, including differences in supply and demand, trading volumes, and regional factors.

Execution Speed: Successful arbitrage requires quick execution because price disparities can be fleeting. Traders who engage in arbitrage often use automated trading bots or algorithms to execute trades rapidly when they identify an arbitrage opportunity.

Risk Mitigation: Arbitrage is considered a low-risk trading strategy because it involves buying low and selling high simultaneously. However, there are still risks involved, such as transaction costs (fees), exchange rate fluctuations, and the time it takes to transfer assets between exchanges.

Types of Arbitrage:

- Spatial Arbitrage: This type of arbitrage involves buying an asset on one exchange or in one geographic location and selling it on another exchange or in a different geographic location where the asset’s price is higher.

- Temporal Arbitrage: Temporal arbitrage takes advantage of price differences over time. For example, a trader may buy an asset when it is undervalued and then sell it when its price has increased, often on the same exchange.

- Statistical Arbitrage: Statistical arbitrage involves the use of statistical models and analysis to identify arbitrage opportunities based on historical price patterns and correlations between assets.

Arbitrage Risks: While arbitrage can be profitable, there are some risks to consider:

- Execution Risk: Delayed execution can lead to missed arbitrage opportunities.

- Market Risk: Prices can change rapidly, erasing potential profits.

- Transaction Costs: Trading fees and transfer fees can reduce profits.

- Regulatory Compliance: Different exchanges may have varying rules and regulations, affecting the ability to transfer and trade assets.

Cryptocurrency Arbitrage: Arbitrage is particularly common in the cryptocurrency markets due to the decentralized and fragmented nature of the crypto exchange ecosystem. Traders look for price differences across various crypto exchanges and take advantage of these opportunities to buy low and sell high.

It’s important to note that while arbitrage can be profitable, it may not always be available or easy to execute, especially as markets become more efficient and technology advances. Traders engaging in arbitrage should have a solid understanding of the markets they are trading in and be prepared to act quickly when opportunities arise. Additionally, they should consider the associated costs and risks when calculating potential profits.

Bear Market

Bear Market is a term used in financial markets to describe a prolonged period during which the prices of assets, such as stocks or cryptocurrencies, experience a significant and sustained decline. In a bear market, investor sentiment is generally pessimistic, and there is a prevailing belief that prices will continue to fall. Here are some key characteristics and points to understand about bear markets:

Price Decline: The defining feature of a bear market is a substantial and consistent decline in asset prices. This decline can result from various factors, including economic downturns, geopolitical events, or changes in market sentiment.

Duration: Bear markets are typically characterized by their duration, often lasting several months or even years. They can be short-lived or extended, depending on the underlying causes and market conditions.

Negative Sentiment: Bear markets are associated with negative sentiment and pessimism among investors. This sentiment can be driven by concerns about economic recession, corporate earnings, or other factors that affect the overall health of the market.

Lower Trading Volume: As prices fall and sentiment turns negative, trading volumes in a bear market often decline. This can be attributed to investors becoming more cautious and less active in the market.

Investor Behavior: In a bear market, investors may become risk-averse and seek safer assets or move their investments into defensive sectors. There is a tendency to sell risky assets like stocks or cryptocurrencies and move into assets considered less volatile or more stable.

Short Selling: Some traders and investors may engage in short selling during a bear market. Short selling involves borrowing and selling an asset with the expectation of buying it back at a lower price, thus profiting from the price decline.

Market Corrections vs. Bear Markets: It’s important to distinguish between a bear market and a market correction. A market correction is a shorter and less severe price decline (usually around 10% or more) that occurs within a generally upward-trending market. A bear market, on the other hand, is a more prolonged and substantial decline.

Causes of Bear Markets: Bear markets can be triggered by a variety of factors, including economic recessions, financial crises, political instability, changes in interest rates, corporate earnings disappointments, or external shocks like natural disasters or geopolitical conflicts.

Investor Strategies: During a bear market, investors may adopt defensive strategies such as reducing their exposure to riskier assets, increasing cash holdings, or seeking alternative investments like bonds or precious metals.

Market Reversal: Bear markets do not last indefinitely. Eventually, economic conditions may improve, and investor sentiment may shift, leading to a market reversal and the start of a new bull market.

Bear markets can be challenging for investors, as they can erode portfolio values and test investors’ emotional resilience. It’s important for investors to have a diversified portfolio and a long-term perspective to navigate bear markets effectively. Additionally, understanding the underlying causes of a bear market and staying informed about economic and market developments is crucial for making informed investment decisions during such periods.

Bull Market

Bull Market is a term used in financial markets to describe a prolonged period during which the prices of assets, such as stocks or cryptocurrencies, experience a significant and sustained increase. In a bull market, investor sentiment is generally optimistic, and there is a prevailing belief that prices will continue to rise. Here are some key characteristics and points to understand about bull markets:

Price Increase: The defining feature of a bull market is a substantial and consistent increase in asset prices. This upward trend can result from various factors, including strong economic growth, corporate profitability, or positive changes in market sentiment.

Duration: Bull markets are typically characterized by their duration, often lasting several months or even years. They can be categorized as short-term or long-term bull markets, depending on their longevity.

Positive Sentiment: Bull markets are associated with positive sentiment and optimism among investors. This sentiment can be driven by strong economic indicators, favourable corporate earnings, or other factors that inspire confidence in the market’s future prospects.

Higher Trading Volume: As prices rise and optimism prevails, trading volumes in a bull market often increase. This reflects increased investor participation as more individuals and institutions seek to capitalize on the rising prices.

Investor Behavior: In a bull market, investors tend to become more risk-tolerant and may allocate a larger portion of their portfolios to riskier assets like stocks or cryptocurrencies. There is a tendency to buy and hold assets with the expectation of further gains.

IPO Activity: Bull markets often see an increase in initial public offerings (IPOs) as companies seek to go public and raise capital while investor appetite is strong.

Market Leadership: Different sectors or asset classes may take the lead during various phases of a bull market. For example, technology stocks or growth-oriented assets may perform exceptionally well in certain bull markets.

Causes of Bull Markets: Bull markets can be triggered by various factors, including low-interest rates, economic expansion, government policies that stimulate economic growth, positive corporate earnings reports, or innovation and technological advancements.

Market Corrections and Pullbacks: While bull markets are characterized by overall rising prices, they can experience temporary setbacks in the form of market corrections or pullbacks. These are relatively short-lived declines before the overall upward trend resumes.

Investor Strategies: During a bull market, investors often focus on growth-oriented strategies, including buying and holding assets, participating in IPOs, or investing in sectors that are expected to benefit from the prevailing economic conditions.

Market Psychology: Bull markets can be influenced by the psychology of investors. As prices rise, more investors become bullish, which can create a self-reinforcing cycle of optimism and buying activity.

It’s important to note that while bull markets can present opportunities for investors to achieve significant gains, they are not without risks. Investors should exercise caution, maintain a diversified portfolio, and be prepared for the possibility of market corrections or reversals. Additionally, staying informed about economic and market developments is essential for making informed investment decisions during bull markets.

Candlestick

Candlestick refers to a graphical representation of price movements within a specific time frame, commonly used in technical analysis to analyze and visualize the price action of financial assets, such as stocks, cryptocurrencies, commodities, or forex pairs. Candlestick charts are a valuable tool for traders and investors to gain insights into market sentiment and potential price trends. Here are key elements and details about candlestick charts:

Components of a Candlestick:

- Body: The rectangular area between the opening and closing prices for a given time frame. It is often referred to as the “real body.” The colour of the body can be used to indicate whether the closing price was higher (usually displayed as green or white) or lower (often displayed as red or black) than the opening price.

- Wick (or Shadow): The thin lines extending above and below the body represent the high and low prices for the same time frame. The upper wick extends from the top of the body to the high price, while the lower wick extends from the bottom of the body to the low price.

Time Frames: Candlestick charts can be plotted for various time frames, such as minutes, hours, days, weeks, or months, depending on the trader’s or analyst’s preference and goals. Each candlestick represents the price action during that specific time frame.

Candlestick Patterns: Patterns formed by one or more candlesticks are used to identify potential price reversals, trend continuations, or other significant market events. Common candlestick patterns include the Doji, Hammer, Shooting Star, Engulfing, and more. These patterns can provide insights into market sentiment and potential future price movements.

Japanese Candlestick Charting: Candlestick charts originated in Japan in the 18th century and gained popularity in the Western world in the 20th century. The Japanese developed and named many of the candlestick patterns used in technical analysis.

Interpreting Candlestick Patterns: Traders and analysts use candlestick patterns in conjunction with other technical indicators and analysis methods to make trading decisions. For example, a “Bullish Engulfing” pattern, where a larger bullish candle completely engulfs the previous bearish candle, may signal a potential reversal from a bearish to a bullish trend.

Single Candlestick Patterns: Some single candlestick patterns can also provide information about market sentiment. For instance, a long lower wick (shadow) on a candlestick may indicate strong buying pressure, as the price moved significantly lower but rebounded by the close of the time frame.

Multi-Candlestick Patterns: Many candlestick patterns involve multiple candlesticks and may require specific criteria to be met. These patterns can be more complex and often have more significant implications for price trends.

Limitations: While candlestick charts are a valuable tool, they are not infallible. They are just one component of technical analysis, and traders should consider other factors such as volume, trendlines, and fundamental analysis when making trading decisions.

Candlestick charts offer a visual representation of price movements that can help traders and analysts identify potential market turning points and trends. It’s essential for those using candlestick analysis to understand the specific patterns, their interpretations, and how they fit into their overall trading strategies.

Day Trading

Day Trading is a trading strategy in which traders buy and sell financial assets (such as stocks, cryptocurrencies, forex, or commodities) within the same trading day, with the primary objective of profiting from short-term price fluctuations. Day traders do not hold positions overnight; instead, they seek to capitalize on intraday price movements. Here are key details and aspects of day trading:

Short-Term Horizon: Day traders focus on short-term price movements, often holding positions for minutes to hours, but not overnight. They aim to take advantage of price volatility within a single trading session.

High Frequency: Day traders may execute multiple trades throughout the day, seeking to capture small price changes across different assets. High trading frequency requires active monitoring of market conditions.

Market Selection: Day traders can participate in various markets, including stocks, cryptocurrencies, forex, futures, and options. Some traders specialize in a specific market, while others diversify across multiple asset classes.

Risk Management: Day trading involves substantial risk due to the fast-paced nature of intraday trading. Traders commonly use risk management techniques such as stop-loss orders to limit potential losses.

Technical Analysis: Many day traders rely heavily on technical analysis, using chart patterns, technical indicators, and real-time market data to make trading decisions. They seek to identify entry and exit points based on technical signals.

Scalping: Scalping is a subset of day trading characterized by extremely short holding periods, often seconds to minutes. Scalpers aim to profit from tiny price movements and may execute a large number of trades in a single day.

Liquidity: Day traders often focus on assets with high liquidity, as this allows for easier entry and exit from positions without significantly affecting prices.

Margin Trading: Some day traders use margin accounts, which allow them to trade with borrowed funds. While this can amplify profits, it also increases the potential for losses.

Pattern Day Trader (PDT) Rule: In the United States, the PDT rule stipulates that traders with less than $25,000 in their brokerage accounts are limited to making no more than three day trades within a rolling five-day period. This rule aims to protect inexperienced traders from excessive risk.

Psychological Challenges: Day trading can be emotionally challenging due to the rapid decision-making and potential for losses. Traders must maintain discipline, control emotions, and stick to their trading plans.

Education and Training: Many day traders undergo extensive education and training to develop their skills. Some traders use simulated or demo accounts to practice their strategies before trading with real money.

Tax Considerations: Tax treatment of day trading profits and losses varies by jurisdiction. It’s important for day traders to understand the tax implications of their trading activities.

Day trading can be highly profitable for some traders, but it is not without risks. Success in day trading often depends on a combination of technical analysis skills, risk management, discipline, and the ability to adapt to rapidly changing market conditions. Traders should be aware of the potential for substantial losses and consider their risk tolerance before engaging in day trading activities.

FOMO (Fear of Missing Out)

FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) is a psychological phenomenon commonly observed in financial markets, particularly in the context of investing and trading. It describes the irrational fear and anxiety that individuals experience when they see others profiting from an investment or asset, and they feel compelled to join in to avoid missing out on potential gains. Here are some key aspects of FOMO:

Herd Mentality: FOMO often results from a herd mentality, where individuals follow the crowd or mimic the actions of others without conducting thorough research or analysis. They may see friends, colleagues, or online influencers making profits and want to participate in the same opportunity.

Timing Pressure: FOMO is often driven by a sense of urgency and the fear that an investment opportunity will disappear or become less profitable if one doesn’t act immediately. Traders under the influence of FOMO may rush into positions without proper due diligence.

Emotional Decision-Making: FOMO can lead to impulsive and emotionally driven investment decisions. Investors may buy assets at elevated prices without considering the underlying fundamentals, valuation, or potential risks.

Volatility Amplification: FOMO-driven buying can temporarily inflate asset prices, leading to short-term price spikes or bubbles. These price increases may not be sustainable, and when FOMO subsides, prices can quickly decline, resulting in losses for late entrants.

Regret Aversion: FOMO is often rooted in a desire to avoid the regret of missing out on significant gains that others have enjoyed. Investors may worry that they will feel left out or remorseful if they do not participate.

Social Media Influence: Social media platforms, forums, and online communities can amplify FOMO by spreading information and excitement about certain assets or investments. The fear of missing out can be magnified through viral content and discussions.

Risk Assessment Neglect: Investors affected by FOMO may neglect proper risk assessment and risk management. They may invest more capital than they can afford to lose or allocate funds to highly speculative assets without considering potential downsides.

Counterproductive Behavior: Ironically, FOMO-driven decisions can often lead to losses rather than gains. Latecomers may purchase assets at peak prices, only to see those prices retreat when the initial hype subsides.

Mitigating FOMO: To mitigate the negative impact of FOMO, it’s important for investors and traders to maintain discipline, conduct thorough research, establish investment goals and strategies, and avoid making decisions solely based on emotional reactions or peer pressure.

FOMO is a powerful psychological force that can influence investment decisions, and it can lead to both positive and negative outcomes. While it may result in short-term gains during market exuberance, it can also lead to significant losses when markets correct or assets experience price reversals. To be successful in investing and trading, individuals should strive to make informed decisions based on sound analysis and risk management principles rather than succumbing to the fear of missing out.

HODL

HODL is a humorous misspelling of the word “hold” that originated from a Bitcoin forum post in 2013. In the context of the cryptocurrency community, especially Bitcoin, it has since become a slang term and meme used to encourage long-term holding of assets rather than actively trading or selling them. Here are some key points about HODL:

Origin: The term “HODL” originated from a post on the BitcoinTalk forum in December 2013. In the post, the author expressed frustration about their inability to time the market and trade successfully. They mistakenly typed “HODL” instead of “hold,” and the term quickly gained popularity within the cryptocurrency community.

Long-Term Holding: HODLing, as encouraged by the term, refers to the strategy of buying cryptocurrencies and holding them for an extended period, often with the belief that the assets will appreciate significantly in the long run. HODLers typically do not engage in frequent trading or attempt to time short-term price movements.

Meme and Community Culture: HODL has become a meme and a part of cryptocurrency culture. It is often used humorously in online discussions and social media posts related to cryptocurrencies. Some people may jokingly refer to themselves as “HODLers” when discussing their investment strategies.

Resisting Short-Term Volatility: HODLers generally believe in the long-term potential of the cryptocurrencies they hold and are willing to endure short-term price volatility without panic-selling. They often view market fluctuations as noise and focus on the larger picture.

Contrast with Traders: The HODLing approach contrasts with active cryptocurrency traders who seek to profit from short-term price movements by buying low and selling high. HODLers typically have a more patient and less active approach to their investments.

Risk and Rewards: While HODLing can potentially lead to significant gains during cryptocurrency bull markets, it also carries the risk of holding assets through prolonged bear markets or substantial price declines. HODLers need to carefully consider their risk tolerance and investment goals.

Diversification: Some HODLers may choose to diversify their cryptocurrency holdings to spread risk across multiple assets. This can help mitigate the impact of poor performance in one cryptocurrency.

HODLing Altcoins: HODL is most commonly associated with Bitcoin, but it can also apply to other cryptocurrencies (altcoins). Some individuals may choose to HODL a mix of Bitcoin and other digital assets.

Long-Term Belief: The essence of HODLing is a long-term belief in the potential of cryptocurrencies to revolutionize finance, technology, or other industries. HODLers often see cryptocurrencies as a disruptive force with the power to change the financial landscape.

It’s important to note that while HODLing can be a valid investment strategy for some individuals, it may not be suitable for everyone. Cryptocurrency markets can be highly volatile, and the choice to HODL should be based on careful consideration of one’s financial situation, risk tolerance, and investment goals. Additionally, it’s essential for investors to stay informed about market developments and periodically reassess their investment strategies.

Liquidity

Liquidity is a fundamental concept in financial markets that refers to the ease with which an asset, such as a stock, bond, commodity, or cryptocurrency, can be bought or sold in the market without causing a substantial change in its price. Liquidity is a critical consideration for traders and investors, and it can significantly impact the efficiency and functionality of a market. Here are some key aspects of liquidity:

Bid and Ask Prices: In a liquid market, there are typically many buyers (demand) and sellers (supply) actively participating. This leads to a narrow bid-ask spread, which is the difference between the highest price a buyer is willing to pay (bid) and the lowest price a seller is willing to accept (ask).

High Trading Volume: Liquid assets are characterized by high trading volumes, meaning a significant number of units of the asset change hands on a regular basis. This high trading activity ensures that there are many buyers and sellers in the market.

Quick Execution: In a liquid market, orders can be executed quickly at or near the current market price. Traders do not have to wait long to buy or sell assets, reducing the risk of price fluctuations during the transaction.

Price Stability: Liquid assets tend to have stable prices because there is a balance between buyers and sellers. Large orders do not significantly move the market, and price changes are generally gradual.

Market Depth: Liquidity is often associated with market depth, which refers to the number of buy and sell orders available at various price levels. A liquid market has significant depth, with many orders at different price points.

Types of Liquidity: There are two primary types of liquidity:

- Market Liquidity: This refers to the ability to buy or sell an asset at the current market price without causing a significant price change. Market liquidity is essential for short-term traders and investors who need to execute orders quickly.

- Asset Liquidity: Asset liquidity refers to the ease of converting an asset into cash without a significant loss in value. Some assets may be less liquid because they are less commonly traded or require time to find a buyer.

Factors Affecting Liquidity: Liquidity can be influenced by various factors, including market participants’ behaviour, news and events, trading hours, and the overall economic environment.

Importance of Liquidity: Liquidity is crucial for the proper functioning of financial markets. It allows investors to enter and exit positions easily, reduces transaction costs, and promotes price efficiency. Liquidity also provides market participants with confidence in the fairness and reliability of the market.

Illiquid Assets: Assets with low liquidity can be challenging to buy or sell without causing significant price swings. Illiquid assets may have wider bid-ask spreads, higher transaction costs, and slower order execution.

Market Orders and Limit Orders: Traders can use market orders to execute immediately at the prevailing market price, which is ideal in liquid markets. In less liquid markets, limit orders, which specify a price at which an asset should be bought or sold, are often used to avoid adverse price movements.

Overall, liquidity is a critical consideration for traders and investors, as it can affect the ease, cost, and efficiency of their transactions. Market participants should assess the liquidity of assets they intend to trade and adjust their strategies accordingly to minimize the impact of liquidity constraints.

Market Order

Market Order is a type of order used in financial markets to buy or sell an asset at the best available current market price. When a trader places a market order, they are essentially instructing their broker or trading platform to execute the order immediately at the prevailing market price, regardless of the specific price level. Here are key details and characteristics of market orders:

Immediate Execution: Market orders are executed as quickly as possible, typically within seconds, as they prioritize speed over price. The goal is to fill the order immediately by matching it with existing buy or sell orders in the market.

No Price Specification: Unlike limit orders (which specify a particular price at which the order should be executed), market orders do not specify a price. Instead, they rely on the current market conditions to determine the execution price.

High Probability of Execution: Market orders are highly likely to be filled because they seek to match with existing orders in the market, regardless of whether it’s a buy or sell order.

Slippage: Market orders may experience slippage, which occurs when the execution price deviates slightly from the expected market price. Slippage can happen when there is a sudden change in market conditions, such as high volatility or low liquidity.

Use Cases: Market orders are commonly used when traders prioritize speed and certainty of execution over getting a specific price. They are suitable for assets with high liquidity and when the trader’s primary concern is entering or exiting a position quickly.

Market Impact: Large market orders can have a significant impact on the asset’s price, especially in less liquid markets. Traders with substantial positions may consider using alternative order types, such as limit orders or algorithmic trading strategies, to minimize market impact.

Risk Management: While market orders offer immediate execution, they do not provide price protection. Traders should be aware that they may receive an execution price different from the last traded price, which can result in unexpected gains or losses.

Fees: Transaction costs associated with market orders may include trading commissions, exchange fees, and spreads (the difference between the bid and ask prices). Traders should consider these costs when using market orders.

Market Buy and Market Sell Orders: Market orders can be categorized into two types: market buy orders and market sell orders. A market buy order instructs the broker to buy the asset immediately at the current market price, while a market sell order instructs the broker to sell the asset at the best available current market price.

Availability: Market orders are widely available on trading platforms and are one of the simplest and most commonly used order types in financial markets.

Market orders are a straightforward way to enter or exit positions quickly, but traders should exercise caution when using them, especially for larger orders or in volatile markets. Slippage and potential market impact should be considered, and in some cases, limit orders or other advanced order types may be more suitable to achieve specific trading objectives.

Resistance

Resistance is a key concept in technical analysis used to describe a specific price level or zone at which an asset, such as a stock, cryptocurrency, or commodity, tends to encounter selling pressure. This selling pressure is significant enough to halt or slow down the asset’s upward price movement, preventing it from rising further. Resistance levels are often identified on price charts and can have important implications for traders and investors. Here are key details and characteristics of resistance:

Price Ceiling: Resistance acts as a “price ceiling” that temporarily restricts the asset’s ability to move higher. When the asset’s price approaches the resistance level, it tends to face increased selling activity as traders and investors take profits or initiate short positions.

Technical Analysis: Resistance levels are typically identified using technical analysis, which involves studying historical price charts, patterns, and price action. Common technical tools for identifying resistance include trendlines, horizontal support and resistance lines, and various chart patterns like double tops and head and shoulders.

Role Reversal: Resistance levels can also be thought of as “role-reversal” points. A level that previously acted as support (where buying interest outweighed selling pressure) may become a resistance level when the price falls below it and traders now see it as a barrier to further price appreciation.

Multiple Resistance Levels: An asset may encounter multiple resistance levels as it moves higher. These levels can form a “resistance zone” or “resistance cluster” where multiple technical factors align to create a formidable barrier to further price gains.

Breakouts: Traders often pay close attention to resistance levels because breaking above a significant resistance level can signal a potential change in the trend or the start of a bullish phase. Such a breakout may lead to further price appreciation.

Confirmation: Confirmation is important when identifying resistance levels. Traders typically look for multiple instances where the asset’s price has been rejected or halted at a particular level to confirm its significance as resistance.

Volume Analysis: High trading volume at or near a resistance level can provide additional confirmation of its significance. If selling pressure is accompanied by a surge in trading volume, it suggests strong resistance.

Time Frames: Resistance levels can exist on various time frames, from intraday charts to long-term charts. The significance of a resistance level may vary depending on the time frame being analyzed.

Psychological Factors: Psychological factors can contribute to the strength of resistance levels. Round numbers or whole figures (e.g., $100 or $1,000) are often viewed as psychological resistance levels and may attract selling interest.

Dynamic Nature: Resistance levels can evolve over time as market conditions change. Traders should be alert to shifts in the market’s dynamics and adapt their strategies accordingly.

Understanding resistance levels is important for traders and investors as they can help in making informed decisions regarding entry and exit points, stop-loss placement, and risk management. When trading near resistance levels, traders often exercise caution and may look for confirmation of a breakout before taking positions to the upside. Conversely, traders may consider shorting or taking profits near strong resistance levels, as they anticipate selling pressure to potentially limit further upside movement.

Support

Support is a crucial concept in technical analysis used to describe a specific price level or zone at which an asset, such as a stock, cryptocurrency, or commodity, tends to encounter buying interest. This buying interest is strong enough to halt or slow down the asset’s downward price movement, preventing it from declining further. Support levels are often identified on price charts and play a significant role in guiding trading and investment decisions. Here are key details and characteristics of support:

Price Floor: Support acts as a “price floor” or a level that temporarily restricts the asset’s ability to move lower. When the asset’s price approaches the support level, it tends to face increased buying activity as traders and investors perceive it as a favourable price at which to buy.

Technical Analysis: Support levels are typically identified using technical analysis, which involves studying historical price charts, patterns, and price action. Common technical tools for identifying support include trendlines, horizontal support and resistance lines, and various chart patterns like double bottoms and ascending triangles.

Role Reversal: Support levels can also be thought of as “role-reversal” points. A level that previously acted as resistance (where selling pressure outweighed buying interest) may become a support level when the price rises above it, and traders now see it as a buying opportunity.

Multiple Support Levels: An asset may encounter multiple support levels as it moves lower. These levels can form a “support zone” or “support cluster” where multiple technical factors align to create a strong buying interest.

Bounces and Rebounds: When an asset’s price reaches a support level, it often experiences a bounce or rebound as buying interest emerges. This can lead to a temporary reversal in the price trend.

Breakdowns: Traders often pay close attention to support levels because breaking below a significant support level can signal a potential change in the trend or the start of a bearish phase. Such a breakdown may lead to further price declines.

Confirmation: Confirmation is important when identifying support levels. Traders typically look for multiple instances where the asset’s price has bounced off or found support at a particular level to confirm its significance as support.

Volume Analysis: High trading volume at or near a support level can provide additional confirmation of its significance. If buying interest is accompanied by a surge in trading volume, it suggests strong support.

Time Frames: Support levels can exist on various time frames, from intraday charts to long-term charts. The significance of a support level may vary depending on the time frame being analyzed.

Psychological Factors: Psychological factors can contribute to the strength of support levels. Round numbers or whole figures (e.g., $100 or $1,000) are often viewed as psychological support levels and may attract buying interest.

Dynamic Nature: Support levels can evolve over time as market conditions change. Traders should be alert to shifts in the market’s dynamics and adapt their strategies accordingly.

Understanding support levels is essential for traders and investors as they can help in making informed decisions regarding entry and exit points, stop-loss placement, and risk management. When trading near support levels, traders often look for confirmation of a bounce or rebound before taking positions to the upside. Conversely, traders may consider shorting or taking profits near strong support levels, as they anticipate buying interest to potentially limit further downside movement.

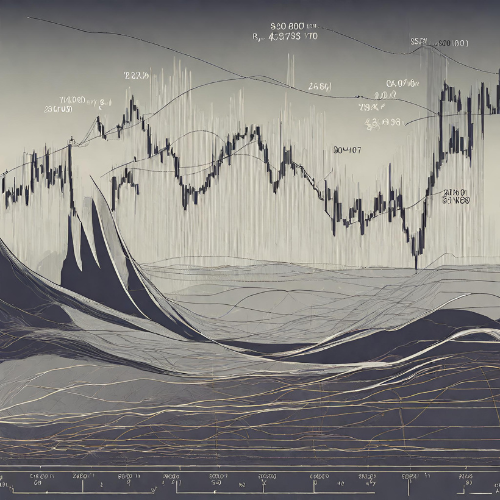

Volatility

Volatility is a fundamental concept in financial markets that measures the degree of price fluctuation of an asset over a specific period of time. It reflects the extent to which an asset’s price moves up and down, and it is often used to assess risk and market dynamics. Here are key details and characteristics of volatility:

Measurement: Volatility is quantified using statistical measures, with the most common measure being standard deviation. Other metrics, such as the average true range (ATR), historical volatility, or implied volatility, may also be used to assess volatility.

Historical vs. Implied Volatility:

- Historical Volatility: This measures an asset’s actual price fluctuations over a specific historical period. It is often calculated using past price data, such as daily or hourly price movements.

- Implied Volatility: Implied volatility reflects market participants’ expectations of future price volatility. It is often derived from the prices of options and can be used to gauge market sentiment and expectations of future price movements.

High vs. Low Volatility:

- High Volatility: Assets with high volatility experience significant price swings over a short period. High volatility can present trading opportunities but also entails greater risk.

- Low Volatility: Assets with low volatility have relatively stable prices and exhibit smaller price movements. Low volatility can be seen as a period of price consolidation.

Causes of Volatility: Various factors can contribute to volatility, including economic data releases, geopolitical events, earnings reports, market sentiment, and unexpected news events. Assets with lower liquidity tend to be more susceptible to extreme price swings.

Volatility Indexes: Volatility indexes, such as the CBOE Volatility Index (VIX), also known as the “fear gauge,” measure market expectations of future volatility in the stock market. They can be used as indicators of market sentiment.

Impact on Trading: Traders and investors consider volatility when making decisions about entry and exit points, stop-loss placement, position sizing, and overall risk management. Higher volatility may require wider stop-loss orders to account for larger price fluctuations.

Volatility Trading Strategies: Some traders specialize in volatility trading strategies, including options trading strategies such as straddles and strangles, which profit from anticipated increases in price volatility.

Asset Classes: Volatility can vary across different asset classes. For example, cryptocurrencies and penny stocks often exhibit higher volatility compared to mature blue-chip stocks or government bonds.

Risk and Reward: While higher volatility can present opportunities for profit, it also carries greater risk. Traders and investors must carefully assess their risk tolerance and adjust their strategies accordingly.

Market Phases: Volatility can change over time and go through phases. Markets may experience periods of low volatility followed by sudden spikes in volatility due to unforeseen events.

Volatility is a natural part of financial markets, and it can create both opportunities and challenges for traders and investors. Understanding an asset’s volatility is essential for making informed decisions, managing risk, and adapting to changing market conditions. Different trading strategies are suited to different levels of volatility, so traders often tailor their approaches to match the market environment.